Lighthouses of Staten Island

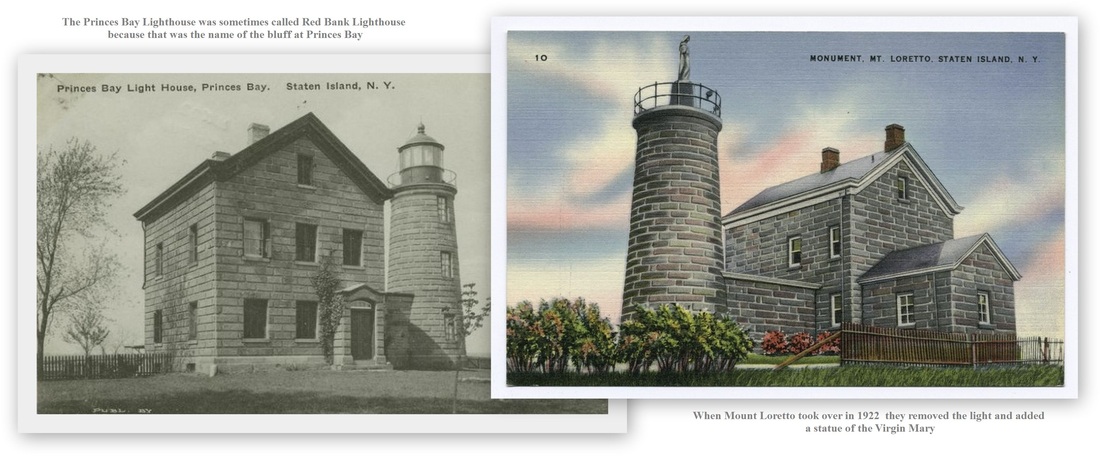

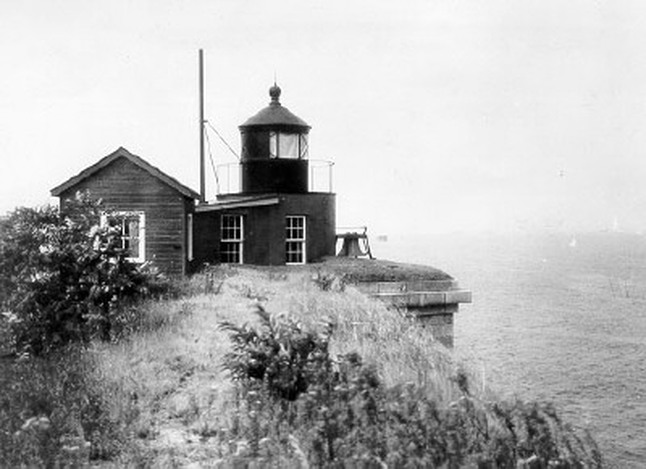

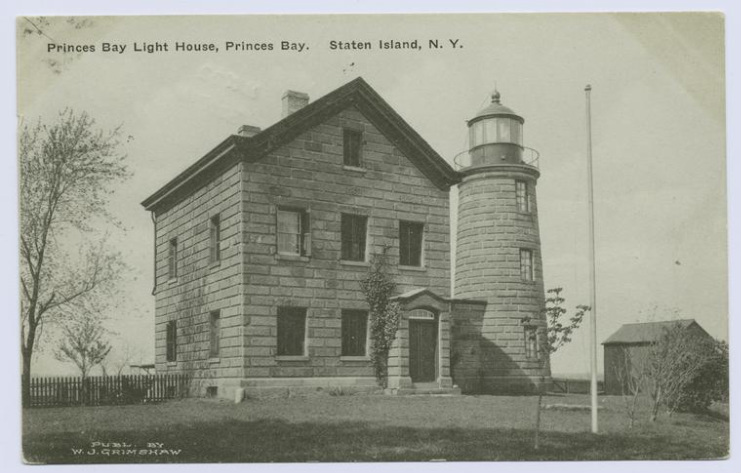

Princes Bay Lighthouse that was on the property of Mount Loretto - after 1922 it was called The Mount Loretto Lighthouse was built in 1864 to serve a large commercial oystering industry and is located on the southern shore of Staten Island, NY near Princes Bay. Deactivated in 1922

The light later became a monument and part of the Mount Loretto Mission of the Immaculate Virgin (a statue of the Virgin Mary is on the tower in place of the lantern.)

During the late 1980s and early 1990s Cardinal John O’Connor, the Archbishop of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York City, spent his summer retreats at this stone structure. The property is now owned by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and in

late 2007, the structure was renamed the John Cardinal O'Connor Lighthouse and a new beacon has been activated as an official aid to navigation.

The light later became a monument and part of the Mount Loretto Mission of the Immaculate Virgin (a statue of the Virgin Mary is on the tower in place of the lantern.)

During the late 1980s and early 1990s Cardinal John O’Connor, the Archbishop of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York City, spent his summer retreats at this stone structure. The property is now owned by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and in

late 2007, the structure was renamed the John Cardinal O'Connor Lighthouse and a new beacon has been activated as an official aid to navigation.

Old Orchard Shoals Light

ABOUT THE OLD ORCHARD SHOALS LIGHTHOUSE - In the late 1800s when winter ice closed down Staten Island Sound, the waterway separating New Jersey from Staten Island, an estimated 15,000 tons of shipping were forced to use the narrow channel that ran along the eastern shore of Staten Island. In doing so, the vessels passed dangerously close to Old Orchard Shoal. A bell buoy and a lighted buoy initially marked this shallow area, but mariners considered these navigational aids grossly inadequate.

The Lighthouse Board asked Congress for funds in 1891 to place a lighthouse on the southeast end of Old Orchard Shoal and to rebuild the tower at Waakcaack, near Keansburg, New Jersey, to serve as a rear range light to the new lighthouse. After $60,000 was approved, construction of the lighthouse was completed in 1893. The new fifty-one-foot, cast-iron tower was cone-shaped, built in the “spark plug” style common among offshore lights in that region. The tower had a canopy over the lower gallery when first built. The tower’s beacon was a fourth-order Fresnel lens, which focused a white beam of light to the southeast, while a red light was shown in the remaining directions. The light, which was first exhibited on April 25, 1893, was on for twelve seconds followed by three seconds of darkness. A fog signal, in the form of an air siren powered by an oil engine, was put in operation at the lighthouse in August of 1896 and sounded blasts of seven-and-a-half seconds followed by a silent interval of the same duration.

The Lighthouse Board asked Congress for funds in 1891 to place a lighthouse on the southeast end of Old Orchard Shoal and to rebuild the tower at Waakcaack, near Keansburg, New Jersey, to serve as a rear range light to the new lighthouse. After $60,000 was approved, construction of the lighthouse was completed in 1893. The new fifty-one-foot, cast-iron tower was cone-shaped, built in the “spark plug” style common among offshore lights in that region. The tower had a canopy over the lower gallery when first built. The tower’s beacon was a fourth-order Fresnel lens, which focused a white beam of light to the southeast, while a red light was shown in the remaining directions. The light, which was first exhibited on April 25, 1893, was on for twelve seconds followed by three seconds of darkness. A fog signal, in the form of an air siren powered by an oil engine, was put in operation at the lighthouse in August of 1896 and sounded blasts of seven-and-a-half seconds followed by a silent interval of the same duration.

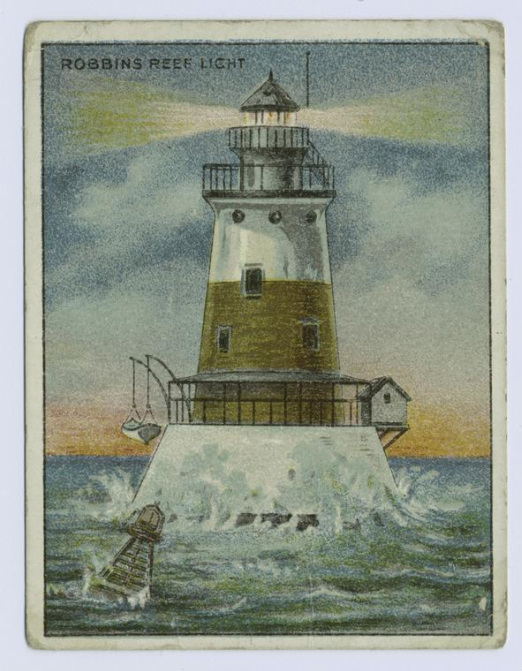

Robbins Reef

"MIND THE LIGHT KATE"

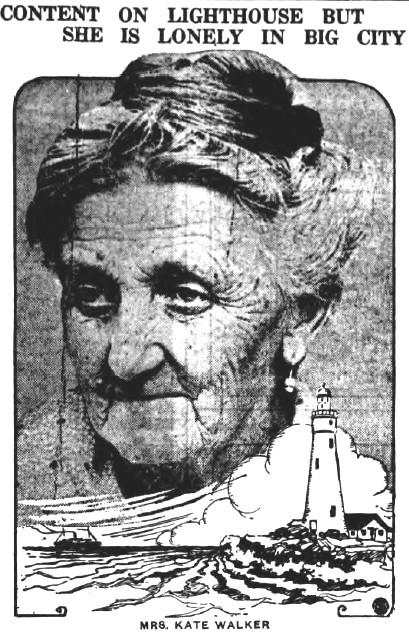

Kate Walker "Lighthouse Kate"

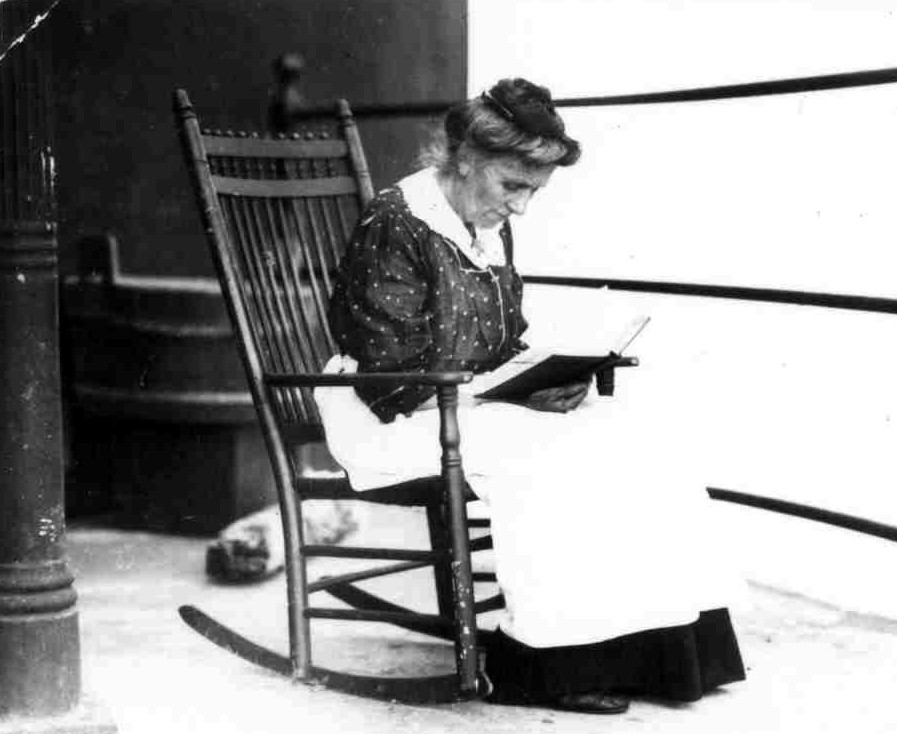

The most famous ladies in New York Harbor is surely Lady Liberty, who first showed up in 1886, just three years after the second Robbins Reef Lighthouse was built. In the lighthouse community, the most famous lady in the New York Harbor was Kate Walker, keeper of Robbins Reef for over thirty years.

To gain an appreciation for Kate Walker, you have to travel back to northern Germany, where she was born Katherine Gortler in 1848. After finishing school, she married Jacob Kaird. The couple's only child, also named Jacob, was only seven years old when his father died. Seeking a new life, Kate took Jacob to America, where she accepted a position waiting tables at a boarding house in Sandy Hook, New Jersey. It was here where she met John Walker, assistant keeper of the Sandy Hook Lighthouse.

Kate knew very little English and gladly accepted Walker's offer of free English lessons. The student-teacher relationship quickly converted into a romantic one, and the two soon married. Kate enjoyed her life at the lighthouse, where there was land for her to grow vegetables and flowers. However, this life was short-lived as John was offered the position as keeper of the recently reconstructed Robbins Reef Lighthouse.

"When I first came to Robbins Reef," Kate recalled, "the sight of the water, which ever way I looked, made me lonesome. I refused to unpack my trunks at first, but gradually, a little at a time, I unpacked. After a while they were all unpacked and I stayed on." John received an annual salary of $600, while Kate was paid $350 to serve as his assistant. The couple, along with their son and new daughter Mary, quickly adjusted to their home with a 360-degree harbor view.

Tragedy touched the station in 1886, when John contracted pneumonia. As he was being taken ashore to a hospital, his parting words to his wife were "Mind the light, Kate." John never returned to his family. For the second time in her life, Kate was a widow, but she carried on, motivated by the need to provide for her two children and fulfill her husband's wish. "Every morning when the sun comes up," Kate said, "I stand at the porthole and look towards his grave. Sometimes the hills are brown, sometimes they are green, sometimes they are white with snow. But always they bring a message from him, something I heard him say more often than anything else. Just three words: 'Mind the light.' "

Although Kate had capably served as assistant keeper, the position of head keeper was only offered to her after two men had turned down it down. Perhaps the Lighthouse Service doubted a petite, 4'10" woman, with two dependent children, could handle the job - and a tough job it was. Every day, Kate would row her children to school, record the weather in the logbook, polish the brass, and clean the lens. At night, she would wind up the weights multiple times to keep the fourth-order lens rotating, trim the wicks, refill the oil reservoir, and in times of fog, she would have to start up the steam engine in the basement to power the fog signal. As her son John matured, he started to help with the tasks and was later made an assistant.

Besides keeping the lighthouse in fine order, Kate also rowed out to assist distressed vessels and is credited with having saved fifty lives. Most of her rescues were fishermen whose boats were blown onto the reef by sudden storms. Kate observed, "Generally, they joke and laugh about it. I've never made up my mind whether they are courageous or stupid. Maybe they don't know how near they have come to their Maker, or perhaps they know and are not afraid. But I think that in the adventure they haven't realized how near their souls have been to taking flight from the body."

After several years, Kate was more at home in the lighthouse than on land, and she was well acquainted with her nearest neighbors, the boats that frequently passed by her kitchen window. Recalling trip she had made to New York City, Kate stated, "I am in fear from the time I leave the ferryboat. The street cars bewilder me and I am afraid of automobiles. Why, a fortune wouldn't tempt me to get into one of those things!" Upon hearing the noon whistle sound at a factory during one of her trips to the big city, she remarked, "If I hadn't known that the Richard B. Morse had been scrapped many years ago, I would have said that was that ship's whistle." It was later determined that the whistle was indeed from the Morse. After a scrap dealer purchased the ship, the whistle was salvaged and sold to the factory.

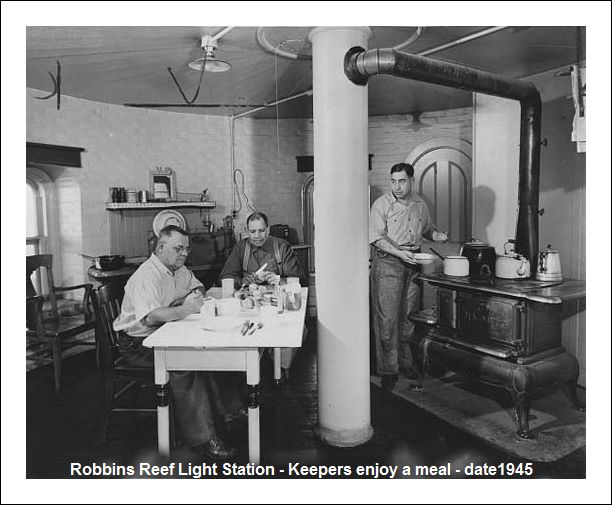

When the Coast Guard assumed responsibility for Robbins Reef Lighthouse in 1939, a three-man crew lived in the lighthouse to perform the duties that not too many years prior had been carried out by the diminutive Kate Walker. In tribute to the heroic service offered by lighthouse keepers, each vessel in the Coast Guard's fleet of fourteen, 175-foot Keeper Class Buoy Tenders is named after a keeper. The KATHERINE WALKER (WLM 552) was launched on September 14th, 1996, and appropriately, its homeport is in Bayonne, New Jersey, within sight of Robbins Reef Lighthouse.

Kate served at the light until 1919, and then retired to nearby Staten Island where she could still keep an eye on the beacon. Even after her retirement and eventual passing in 1935 at the age of eighty-four, captains and harbor pilots still referred to the lighthouse as "Kate's Light."

To gain an appreciation for Kate Walker, you have to travel back to northern Germany, where she was born Katherine Gortler in 1848. After finishing school, she married Jacob Kaird. The couple's only child, also named Jacob, was only seven years old when his father died. Seeking a new life, Kate took Jacob to America, where she accepted a position waiting tables at a boarding house in Sandy Hook, New Jersey. It was here where she met John Walker, assistant keeper of the Sandy Hook Lighthouse.

Kate knew very little English and gladly accepted Walker's offer of free English lessons. The student-teacher relationship quickly converted into a romantic one, and the two soon married. Kate enjoyed her life at the lighthouse, where there was land for her to grow vegetables and flowers. However, this life was short-lived as John was offered the position as keeper of the recently reconstructed Robbins Reef Lighthouse.

"When I first came to Robbins Reef," Kate recalled, "the sight of the water, which ever way I looked, made me lonesome. I refused to unpack my trunks at first, but gradually, a little at a time, I unpacked. After a while they were all unpacked and I stayed on." John received an annual salary of $600, while Kate was paid $350 to serve as his assistant. The couple, along with their son and new daughter Mary, quickly adjusted to their home with a 360-degree harbor view.

Tragedy touched the station in 1886, when John contracted pneumonia. As he was being taken ashore to a hospital, his parting words to his wife were "Mind the light, Kate." John never returned to his family. For the second time in her life, Kate was a widow, but she carried on, motivated by the need to provide for her two children and fulfill her husband's wish. "Every morning when the sun comes up," Kate said, "I stand at the porthole and look towards his grave. Sometimes the hills are brown, sometimes they are green, sometimes they are white with snow. But always they bring a message from him, something I heard him say more often than anything else. Just three words: 'Mind the light.' "

Although Kate had capably served as assistant keeper, the position of head keeper was only offered to her after two men had turned down it down. Perhaps the Lighthouse Service doubted a petite, 4'10" woman, with two dependent children, could handle the job - and a tough job it was. Every day, Kate would row her children to school, record the weather in the logbook, polish the brass, and clean the lens. At night, she would wind up the weights multiple times to keep the fourth-order lens rotating, trim the wicks, refill the oil reservoir, and in times of fog, she would have to start up the steam engine in the basement to power the fog signal. As her son John matured, he started to help with the tasks and was later made an assistant.

Besides keeping the lighthouse in fine order, Kate also rowed out to assist distressed vessels and is credited with having saved fifty lives. Most of her rescues were fishermen whose boats were blown onto the reef by sudden storms. Kate observed, "Generally, they joke and laugh about it. I've never made up my mind whether they are courageous or stupid. Maybe they don't know how near they have come to their Maker, or perhaps they know and are not afraid. But I think that in the adventure they haven't realized how near their souls have been to taking flight from the body."

After several years, Kate was more at home in the lighthouse than on land, and she was well acquainted with her nearest neighbors, the boats that frequently passed by her kitchen window. Recalling trip she had made to New York City, Kate stated, "I am in fear from the time I leave the ferryboat. The street cars bewilder me and I am afraid of automobiles. Why, a fortune wouldn't tempt me to get into one of those things!" Upon hearing the noon whistle sound at a factory during one of her trips to the big city, she remarked, "If I hadn't known that the Richard B. Morse had been scrapped many years ago, I would have said that was that ship's whistle." It was later determined that the whistle was indeed from the Morse. After a scrap dealer purchased the ship, the whistle was salvaged and sold to the factory.

When the Coast Guard assumed responsibility for Robbins Reef Lighthouse in 1939, a three-man crew lived in the lighthouse to perform the duties that not too many years prior had been carried out by the diminutive Kate Walker. In tribute to the heroic service offered by lighthouse keepers, each vessel in the Coast Guard's fleet of fourteen, 175-foot Keeper Class Buoy Tenders is named after a keeper. The KATHERINE WALKER (WLM 552) was launched on September 14th, 1996, and appropriately, its homeport is in Bayonne, New Jersey, within sight of Robbins Reef Lighthouse.

Kate served at the light until 1919, and then retired to nearby Staten Island where she could still keep an eye on the beacon. Even after her retirement and eventual passing in 1935 at the age of eighty-four, captains and harbor pilots still referred to the lighthouse as "Kate's Light."

Fort Wadsworth Lighthouse

Fort Wadsworth Lighthouse as it looks today

Vanderbilt Tower, New Dorp

The Next 5 photos are the same lighthouse at Miller Field, New Dorp

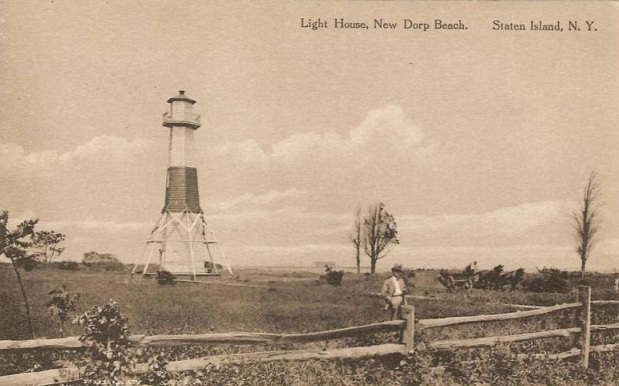

Elm Tree Beacon

ELM TREE BEACON (SWASH CHANNEL FRONT RANGE LIGHT) Location: ON THE SOUTHEASTERLY SIDE OF STATEN ISLAND, WESTERLY SHORE OF NEW YORK LOWER BAY Station Established: 1856 Year Current / Last Tower(s) First Lit: Operational: No Automated: Deactivated: Tower Shape / Markings / Pattern: Wooden tower, painted in bands, two white and one red; roof of lantern, red. Height: 59-1/2 feet Original Lens: Range lens Characteristic: Fixed white Fog Signal: None HISTORICAL INFORMATION: •Served as the Swash Channel Front Range Light; New Dorp Beacon served as the rear range light.

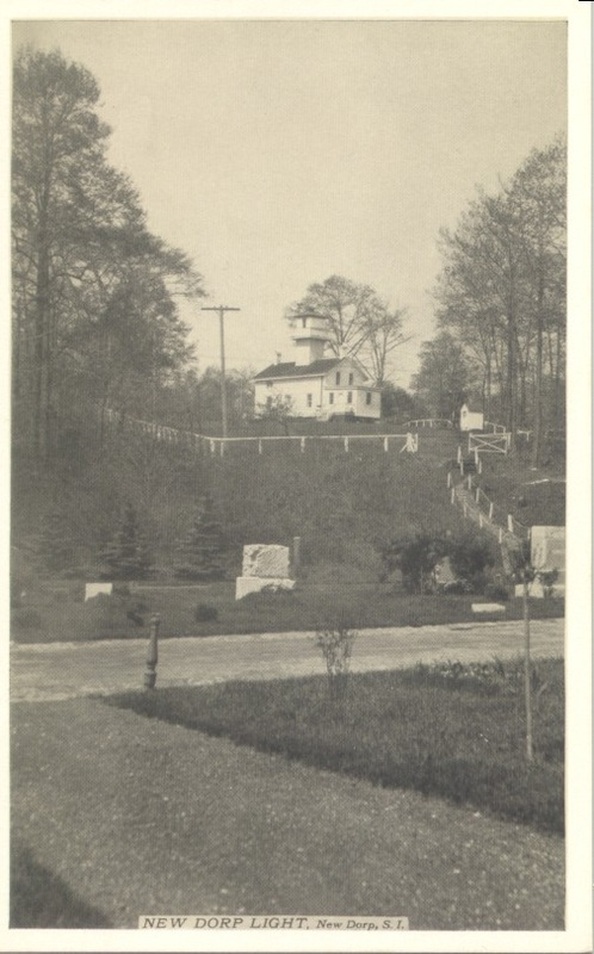

New Dorp Lighthouse 25 Boyle Street NEW DORP (SWASH CHANNEL REAR RANGE) LIGHT STATEN ISLAND/LOWER NEW YORK BAY Station Established: 1856 Year Current Tower(s) First Lit: 1856 Operational? NO Automated? UNK Deactivated: 1964 Foundation Materials: BRICK Construction Materials: WOOD Tower Shape: SQUARE ON CENTER OF DWELLING Markings/Pattern: WHITE Relationship to Other Structure: INTEGRAL Original Lens: SECOND ORDER, FRESNEL 1856 HISTORICAL INFORMATION: •This was the Swash Channel Rear Range Light, the front range light was the Elm Tree Beacon

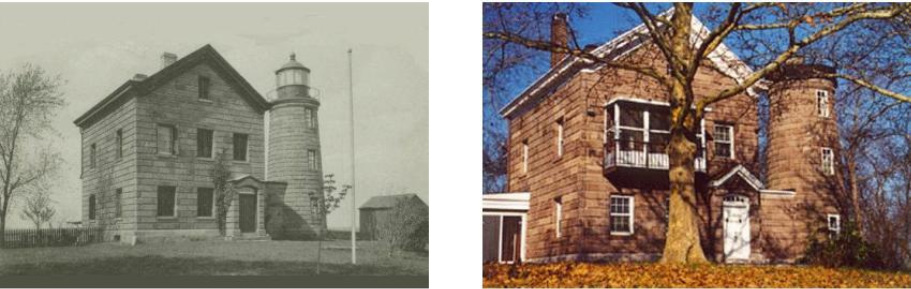

PRINCES BAY LIGHT (OLD)STATEN ISLAND/LOWER NEW YORK BAYStation Established: 1828Year Current Tower(s) First Lit: 1828Operational? NOAutomated? YESDeactivated: 1922Foundation Materials: NATURAL/EMPLACEDConstruction Materials: BROWNSTONE BLOCKSTower Shape: CONICALMarkings/Pattern: NATURALRelationship to Other Structure: ATTACHEDOriginal Lens: THIRD AND ONE HALF, FRESNEL 1857

Fort Tompkins Light

was a lighthouse located on Staten Island, New York City, on the west side of the Narrows in New York Bay.

The lighthouse was established by Fort Tompkins Military Base in 1828 to guide ships to Staten Island. The lighthouse did not keep records due to its close proximity to land. Consequently, very little record survives beyond those kept by the lighthouse board.

The Board archives illustrate the precarious location of the lighthouse. On more than one occasion the lighthouse became a target and various explosions caused the glass in the lantern room to break. They moved the lighthouse in 1871 out of battery range and was not near the water.

Its first light in the new location was in 1872. A fourth order Fresnel lens was installed in 1900. The light was an alternate flashing red and white with an interval between flashes of 10 seconds. Three years later the lighthouse was deactivated. The lighthouse's duties were given to the Fort Wadsworth Light in 1903. Soon after, the lighthouse was abandoned. It no longer exists.

The tower stood on a Victorian-style home with a white dwelling, Mansard roof and a black lantern

Below to the left is a photo of the

actual light but sadly it no longer stands...

to the right is a model

created by Joe Esposito...his models are so life like

that it is impossible to tell which is

the actual and which is the model...

was a lighthouse located on Staten Island, New York City, on the west side of the Narrows in New York Bay.

The lighthouse was established by Fort Tompkins Military Base in 1828 to guide ships to Staten Island. The lighthouse did not keep records due to its close proximity to land. Consequently, very little record survives beyond those kept by the lighthouse board.

The Board archives illustrate the precarious location of the lighthouse. On more than one occasion the lighthouse became a target and various explosions caused the glass in the lantern room to break. They moved the lighthouse in 1871 out of battery range and was not near the water.

Its first light in the new location was in 1872. A fourth order Fresnel lens was installed in 1900. The light was an alternate flashing red and white with an interval between flashes of 10 seconds. Three years later the lighthouse was deactivated. The lighthouse's duties were given to the Fort Wadsworth Light in 1903. Soon after, the lighthouse was abandoned. It no longer exists.

The tower stood on a Victorian-style home with a white dwelling, Mansard roof and a black lantern

Below to the left is a photo of the

actual light but sadly it no longer stands...

to the right is a model

created by Joe Esposito...his models are so life like

that it is impossible to tell which is

the actual and which is the model...

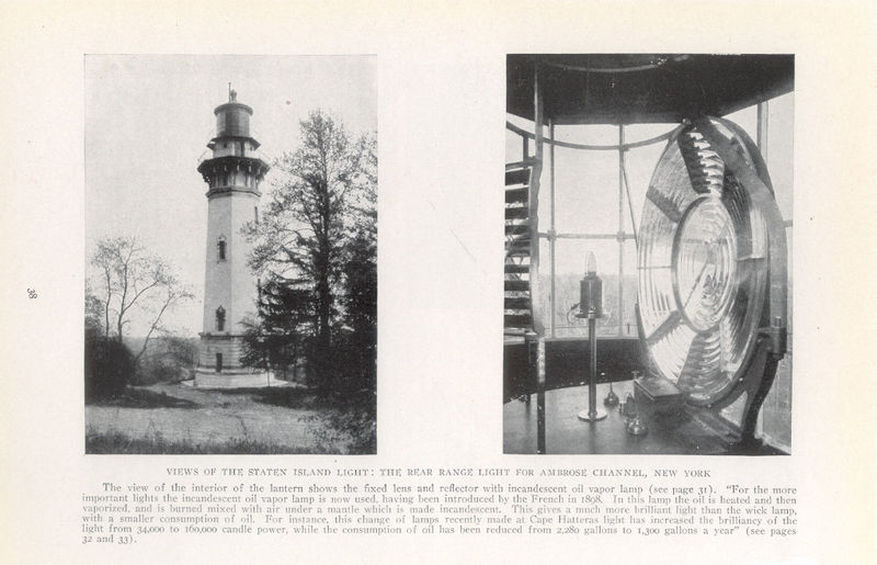

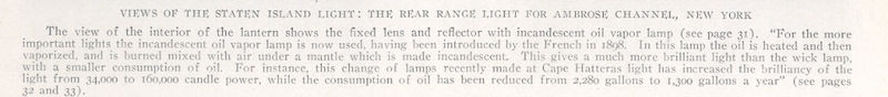

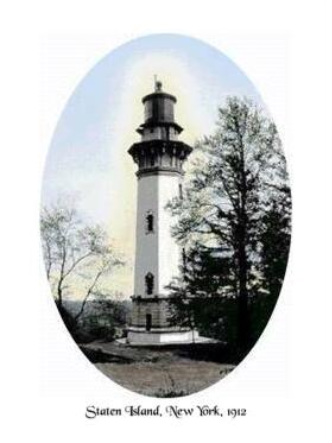

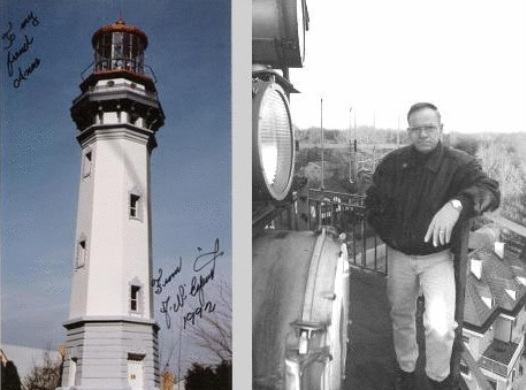

Staten Island Lighthouse

& its carekeeper Joe N Esposito

Joseph N. Esposito, lighthouse historian and preservationist and for more than nine years the caretaker of New York’s Staten Island Lighthouse, was recognized on April 18, 2001 by the Coast Guard in a citation awarded for meritorious service. Esposito had to step down from the volunteer position due to medical problems. Reflecting on the end of his lighthouse duties, Esposito says, “I feel like I’ve lost a dear friend.”

The Certificate of Merit from Rear Admiral Richard E. Bennis, U.S. Coast Guard Activities, New York, stated that the 62-year-old Esposito’s “hard work on this proud remnant of Staten Island and Coast Guard history is sincerely appreciated...” and goes on to say that Esposito has “upheld the highest traditions of the United States Coast Guard.”

Esposito returns the compliment, saying, “The Coast Guard was good to me. They would always send me whatever I needed to help out with this light. They would always say that I was part of the team. That made me feel good.”

Esposito is a master electrician, carpenter and mason by trade. Back in 1992 after major Coast Guard budget cuts, he asked about the possibility of becoming the caretaker of the lighthouse. Esposito submitted his resumé and soon had the keys to the tower. “He’s been wonderful,” Rear Admiral Bennis told the New York Times. “We were lean and mean and we needed someone to take care of the place.”

During his years as caretaker Esposito did everything from cutting the small patch of grass around the tower to explaining the station’s history to visitors, as well as making sure the light was operating 24 hours a day. On the rare occasions that the light went out, residents of Lighthouse Hill would quickly let Esposito know and he would fix whatever needed fixing.

The handsome buff-colored 90-foot Staten Island tower was designated a New York City Landmark in 1968 and is one of the last brick lighthouses built in the United States. Esposito told the New York Times, “I’m gonna miss her. She’s the only one like it in the world.” Staten Island Light serves as a rear range light with the West Bank Lighthouse, guiding vessels into the bay. The lighthouse is in good condition inside and out, and Esposito says, “Every time I stepped in it, I was going back in time to 1912.”

For many years Joe Esposito has also constructed some of the most detailed lighthouse replicas in existence. He says he makes the models “so I can see the light when I can’t really be there.” In 1992 he spent three months completing a three-foot seven-inch model of Staten Island Lighthouse, and he recently donated the model to Staten Island’s National Lighthouse Museum, still in the formative stages.

It isn’t clear whether or not the Coast Guard will designate a new caretaker for Staten Island Lighthouse or simply do the work themselves. What is clear is that Joe Esposito’s name will long remain tied to this important piece of New York and American lighthouse history. He has “kept a good light” in the best tradition of the Coast Guard.

The Certificate of Merit from Rear Admiral Richard E. Bennis, U.S. Coast Guard Activities, New York, stated that the 62-year-old Esposito’s “hard work on this proud remnant of Staten Island and Coast Guard history is sincerely appreciated...” and goes on to say that Esposito has “upheld the highest traditions of the United States Coast Guard.”

Esposito returns the compliment, saying, “The Coast Guard was good to me. They would always send me whatever I needed to help out with this light. They would always say that I was part of the team. That made me feel good.”

Esposito is a master electrician, carpenter and mason by trade. Back in 1992 after major Coast Guard budget cuts, he asked about the possibility of becoming the caretaker of the lighthouse. Esposito submitted his resumé and soon had the keys to the tower. “He’s been wonderful,” Rear Admiral Bennis told the New York Times. “We were lean and mean and we needed someone to take care of the place.”

During his years as caretaker Esposito did everything from cutting the small patch of grass around the tower to explaining the station’s history to visitors, as well as making sure the light was operating 24 hours a day. On the rare occasions that the light went out, residents of Lighthouse Hill would quickly let Esposito know and he would fix whatever needed fixing.

The handsome buff-colored 90-foot Staten Island tower was designated a New York City Landmark in 1968 and is one of the last brick lighthouses built in the United States. Esposito told the New York Times, “I’m gonna miss her. She’s the only one like it in the world.” Staten Island Light serves as a rear range light with the West Bank Lighthouse, guiding vessels into the bay. The lighthouse is in good condition inside and out, and Esposito says, “Every time I stepped in it, I was going back in time to 1912.”

For many years Joe Esposito has also constructed some of the most detailed lighthouse replicas in existence. He says he makes the models “so I can see the light when I can’t really be there.” In 1992 he spent three months completing a three-foot seven-inch model of Staten Island Lighthouse, and he recently donated the model to Staten Island’s National Lighthouse Museum, still in the formative stages.

It isn’t clear whether or not the Coast Guard will designate a new caretaker for Staten Island Lighthouse or simply do the work themselves. What is clear is that Joe Esposito’s name will long remain tied to this important piece of New York and American lighthouse history. He has “kept a good light” in the best tradition of the Coast Guard.

Many of the photos on this page are courtesy of

Anne Marie - Lady in Loft Productions,

http://domania.us/ladyinloft/index.html

it is through her that Joe Esposito sent

some of his wonderful model photos

(above is the story about Joe)

Anne Marie - Lady in Loft Productions,

http://domania.us/ladyinloft/index.html

it is through her that Joe Esposito sent

some of his wonderful model photos

(above is the story about Joe)

Please sign our guestbook below

let us know what you think about

this Old Staten Island Website

let us know what you think about

this Old Staten Island Website