Staten Island Ferry History

This page was inspired by the many donated photos from the collection of

John Landers and Beth Klein

(Most photos are this page are clickable to view as a lightbox - Bigger & Brighter)

John Landers and Beth Klein

(Most photos are this page are clickable to view as a lightbox - Bigger & Brighter)

A letter to me from John Landers about his love of ferry's . . . .

John:

My Staten Island Ferry interest began in the mid 1960's taking the boats over to visit relatives in Great Kills. I would beg my mother to "please let's wait for the next boat" if the one we were scheduled to ride was the Pvt. Joseph F Merrell, Verrazzano or the Cornelius G. Kolff in hopes of the next one being the Gold Star Mother, Miss New York or Mary Murray. I simply liked the older vessels from my earliest days. There was a warmth to them I just didn't feel on the larger and newer boats. Walking on to the Miss New York you could just feel the antiqueness to it. The stained glass signs separating MEN and WOMEN to different sides of the boats seemed odd to me. At first glance one might think the sexes were being segregated, but the real explanation was a very innocent one. In the early days of NYC ferry travel one side of the boat had the men's toilet and the other side had the women's toilet and the signage was to assist passengers so they could easily locate the correct facility without having to encircle the entire vessel. Later after these boats were retrofitted with multiple bathrooms on each side the MEN and WOMEN sides became SMOKING and NO SMOKING sides. Another part of New York City history gone forever. Over the years I have made friends with many NY Ferry historians and traded or purchased photos from them or at NYC themed paper shows to the point of having established a very nice collection. Oddly in my very early days of collecting ferryboat and FDNY Fireboat photos I found other collectors treated their photos as if they were gold bricks and would rarely share them with other collectors. This mind set always baffled me and I promised myself that if I were ever to amass a large and respectable collection of nice photos I would share them with anyone interested with no restrictions. My logic was simple in that getting a photo I never saw before gave me a great feeling and I wanted others who might be interested either for research or for pleasure to experience the same joys I did. Being a lifelong New Yorker and having grown up in Brooklyn (with a short 4 year move to Stuyvesant Town in Manhattan) my love of the City's rich history extends to not just the ferries but to the subway and buses as well. This history fascinated me so much I began collecting NYC maps, eventually collecting well over 5000. One of my dearest friends and mentors is a man by the name of Stan Fischler who in addition to being The Hockey Maven, is also a walking encyclopedia on the New York City Subway system. One thing Stan taught me early on is "If you know where to look and HOW to look (and HOW is the more difficult part) you can still see bits and pieces of New York City Transit history oblivious to the eye of the regular New Yorker". Stan encouraged me to take my enormous map collection and share it with all in the form of a book. He introduced me to the late John Henderson, who was a transportation book publisher and soon TWELVE HISTORICAL NEW YORK CITY STREET AND TRANSIT MAPS was on sale in hundreds of bookstores. It was such a successful and pleasurable venture that I eventually did a second volume. Beth Klein is a school teacher and my wife for nearly ten years. I am an extremely lucky man to have such a wonderful partner. She not only allows me to enjoy the cities rich history she encourages me and has joined me in walking over every bridge within the five boroughs that allows for foot traffic. One weekend several years ago we walked over the Brooklyn, Manhattan, Williamsburg, Queensboro, Randalls Island and Triboro Bridges all in the same day. It took us over 20 hours but touring the city in this manner was priceless and I highly recommend it to all. I have always been of the belief if your vocation and avocation are one and the same you are an extremely lucky person. My love affair with New York City Transit led me to becoming a Subway Conductor having subsequently been promoted to Tower Operator. This has allowed me virtual unlimited access to areas off limits to most yet still rich with history. I hope you enjoy these contributions from my collection.

I wish to thank John Louis Sublett and his wonderful website www.StatenIslandHistory.com for allowing this Brooklynite the opportunity to share and preserve Staten Island's wonderful history.

John Landers and Beth Klein - Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, NY

The bronze one was INTENDED to be used for regular passenger service and the silver one was INTENDED to be used for passengers with bicycles.

The SI Ferry token program was never implemented.

The SI Ferry token program was never implemented.

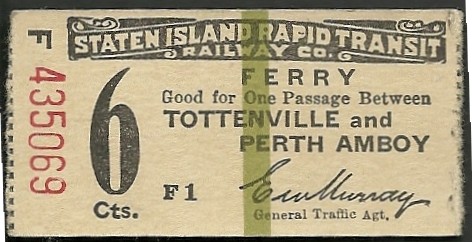

Below are a few paper tickets for the ferries

The following 5 photos show ferries named after the 5 boroughs

(all from the collection of John Landers and Beth Klein)

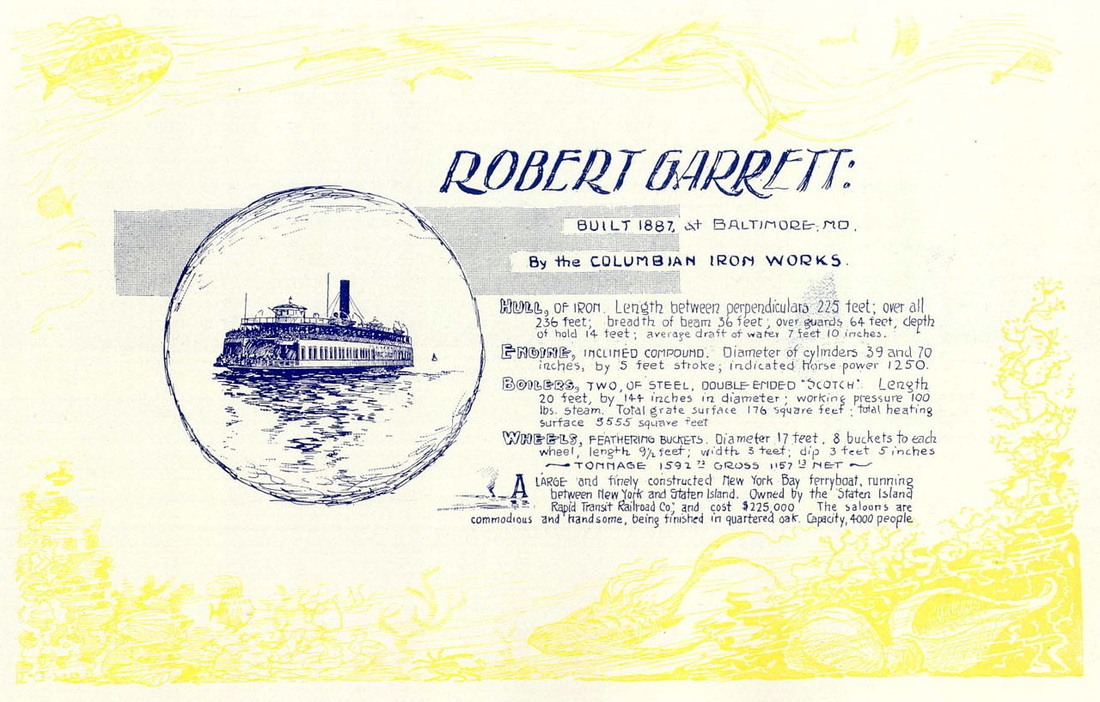

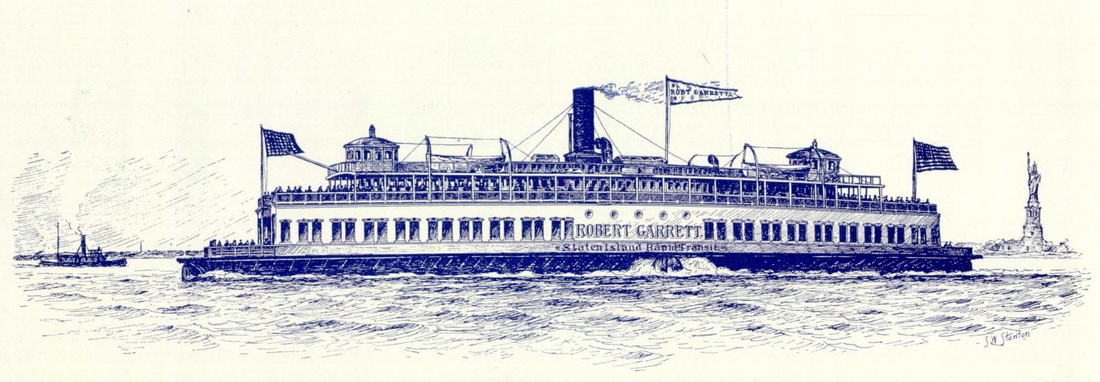

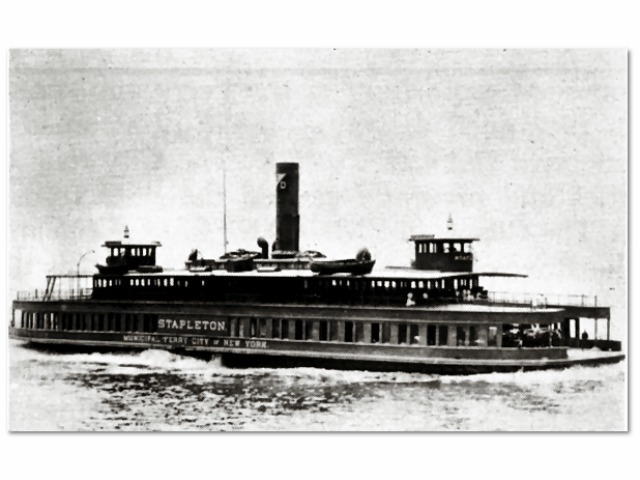

The paddlewheeler Robert Garrett was one of the ferryboats the Staten Island Rapid Transit Railway operated between

St. George and Manhattan when the Island became part of the Greater City of New York in 1898.

(click on the photos below for a larger view)

St. George and Manhattan when the Island became part of the Greater City of New York in 1898.

(click on the photos below for a larger view)

In later years the Robert Garrett became the Stapleton

The three ferries below were all from the Tottenville to Perth Amboy line

(Maid of Perth, Perth Amboy and Charles Galloway)

The Perth Amboy ferry line was first operated in June 1860 with steamboats, the first true ferryboat was the Maid of Perth, which set sail in 1867. The ferry was a profitable enterprise as an adjunct to the Staten Island Rapid Transit. Even after the Outerbridge Crossing opened in 1928, it continued as a profitable project because of its frequent and reliable service over a period of 81 years.

This company’s last ferry, the Charles Galloway, left Pert Amboy for Tottenville on Oct. 16, 1948. Smaller boats provided subsequent ferry service until 1963, when this service between Staten Island and New Jersey ended.ice over a period of 81 years.

(Maid of Perth, Perth Amboy and Charles Galloway)

The Perth Amboy ferry line was first operated in June 1860 with steamboats, the first true ferryboat was the Maid of Perth, which set sail in 1867. The ferry was a profitable enterprise as an adjunct to the Staten Island Rapid Transit. Even after the Outerbridge Crossing opened in 1928, it continued as a profitable project because of its frequent and reliable service over a period of 81 years.

This company’s last ferry, the Charles Galloway, left Pert Amboy for Tottenville on Oct. 16, 1948. Smaller boats provided subsequent ferry service until 1963, when this service between Staten Island and New Jersey ended.ice over a period of 81 years.

The Maid of Perth

The Perth Amboy - date 1946

The Charles W Galloway - date 1947

(The photos of the Perth Amboy and Charles Galloway are the only two color photos known to exist of these vessels while still in passenger service.)

(The photos of the Perth Amboy and Charles Galloway are the only two color photos known to exist of these vessels while still in passenger service.)

Ferryboat Astoria

Ferryboat Atlantic

Ferryboat Fordham

Ferryboat Rodman Wanamaker

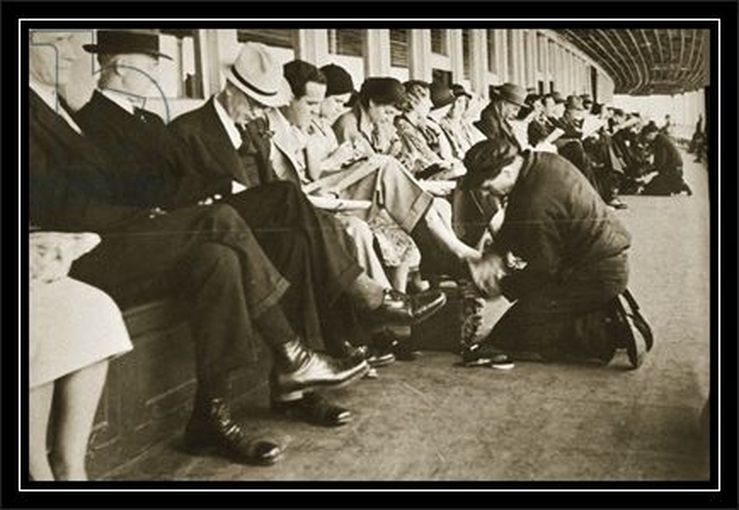

A big part of SI Ferry History was the shoeshine guys, here is a story about them

The Staten Island Ferry continues to hum across the jelly-like waters, back and forth. The engine's reverberations still massage your feet. The smell of overcooked hot dogs still consumes the concession stand. And the ride still ends with the groan of massive vessel meeting wooden slip, the sound of journey's end.

But one sound has gone missing from the ferry experience these past few months. This sound: Shine! Shine! Wanna shine?

For more than 30 years, an Italian immigrant named Carmine Rizzo walked up and down the worn aisles of the ferries, calling out his services and hoping for the catch of an eye, the raise of a hand, a simple nod. Once summoned, he would place a small pillow on the ground and kneel before the patron, as if in supplication.

From this vantage point he could not see the glint of morning sunlight off Lady Liberty's torch, or gaze into the fog that seems to set the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge in the backdrop of a dream. There on his knees, all he saw were the words ''Life Preservers'' stenciled beneath the lips of scarred, dark-wooded benches; trouser legs; and other people's shoes.

He and a couple of other men from the Salerno region of Italy detected opportunity in the desire of businessmen to exude financial promise, down to the very tips of their shoes. These immigrants hawked and polished and buffed, marking the years through their faint reflections in footwear. One by one they disappeared, though, dying or retiring or returning to Italy, until there was only Mr. Rizzo, calling out shine, shine, above the ferry hum.

With the demand for polished shoes in decline, and the modest potential for making money, Mr. Rizzo retired four years ago -- only to return three weeks later. Then, in December, he retired again, telling The Staten Island Advance that at the age of 76, he saw no benefit in commuting from Whitestone, Queens, early in the morning to make as little as $2.50 a shine.

''This time I'm firm,'' he had said through an interpreter. ''I'm not coming back.''

The city's Department of Transportation had no choice but to advertise the availability of a city concession. It issued a 38-page document entitled ''Request for Bids for the Operation of a Roving Shoe Shine Service on the Staten Island Ferry Boats.''

The document detailed the potential of the enterprise, explaining, for example, that 65,000 commuters and tourists ride the ferries that chug to and from Manhattan and the St. George section of Staten Island. It asked bidders to ride the ferry, ''which is free, to view the passenger seating areas.''

It also laid out the ground rules for a ferryboat shoe shiner. The licensee ''may offer services with a short verbal announcement that includes the price of service (i.e. 'Shoe Shine! X Dollar Shoe Shine!'),'' it said, but may not be ''loud, offensive, misleading or unduly intrusive.''

For the right to get down on your knees, again and again, and polish the shoes of those whose faces are often concealed behind newspapers, the city suggested a minimum bid of $4,000 for the first year. Bids were to be submitted no later than 11 a.m. on Jan. 12, the document said, at which time they would be ''opened promptly.''

At 11 a.m. that day, city officials promptly opened nothing. ''We didn't get any bid,'' Tom Cocola, a transportation spokesman, said. ''It's as simple as that.''

What did this silence mean? Were up-and-coming entrepreneurs missing the opportunity of a lifetime? After all, people still wear shoes, and more than a few still want others to shine their shoes for them.

Perhaps there is something off-putting, even sad, about a shoeshine man without permanent station: a man who carries his wooden shoe stand and pillow through the aisles and decks of a swaying city ferry, waiting for the wave that permits him to kneel. If his presence evokes an Old New York charm, perhaps it is only to those whose shoes sparkle.

FOR nearly five months now, the Staten Island Ferry has borne the absence of the shoeshine man who speaks virtually no English. But the city recently announced that it was trying once again to solicit bids for shoeshine service on the ferries. Interested parties can submit their bids on June 1.

Word of this new solicitation for bids has reached a certain household on solid ground in Whitestone, where a recent retiree putters about, unable to relax.

''He's driving me crazy,'' said Angelo Rizzo of his father. ''Up the wall, sometimes.''

Some days Carmine Rizzo thinks no, the son says. But other days he thinks yes, yes, he should return to roving the ferry.

In 2000 Carmine Rizzo retired as a shoeshine guy on the SI Ferry but Carmine did not take a shine to retirement.

The ferry shoeshine guy was back in business, just three weeks after telling the city Department of Transportation (DOT) he did not intend to renew his long-standing concession contract to provide services inside the St. George terminal and aboard the boats.

But there he was yesterday morning, kneeling on his raggedy pillow, hunched over a pair of black loafers belonging to a well-dressed man sitting by the snack bar on the 10:30 Manhattan-bound Gov. Herbert H. Lehman.

"It's not good at home," Rizzo said in his halting Italian accent after finishing the job. "Working

three days only." As Rizzo cruised to Manhattan, his spitshine sidekick, Angelo Passero, was buffing his way to

St. George aboard the Samuel I. Newhouse, according to Lehman crew members.

Yesterday was the first day back on the boats for the shoeshine guys since Jan. 5, when Rizzo's $7,200-a-year DOT concession contract expired.

Apparently bored with a life of leisure, Rizzo recently signed a new one-year, $7,600 contract, effective yesterday, to provide shoeshine services aboard the boats three days a week, according to a DOT spokesman.

Last week, the DOT removed the decrepit shoeshine stand Rizzo once rented outside the ladies' room at the St. George terminal, the spokesman said. It was not immediately clear whether the stand will return.

Though Staten Island Ferry staples for decades, little is known about Rizzo and Passero. The pair -- who bear a striking resemblance to one another and are often confused as being the same man or brothers -- have long rebuffed interview-seeking Advance reporters.

Rizzo reportedly lives in Queens; Passero in Brooklyn. Both men hail from the same Italian province, Salerno, and communicate with passengers only in terse phrases of limited English.

When pressed for details on what exactly was "not good" about retirement, Rizzo said daily episodes of his grandchildren crashing on his sofa wore thin fast. "Sit and watch TV all day," he said, dismissing the very thought of idleness

with a wave of his large, weathered hand. Then, with a sparkle in his eye and a wry smile, Rizzo nodded emphatically

when asked if it felt good to be back on board.

Lehman crew members and ferry patrons also expressed delight at the shoeshine guy's decision to shelve retirement.

"I was shocked to see him," said a deckhand who lives on the South Shore but refused to identify himself. "It's good to see [the shoeshine guys] back. They've been here so long. They're like half the family."

"I missed him the three weeks he was gone," Colleen Mooney, of Port Richmond, a longtime ferry attendant, said of Rizzo. "He's like one of the crew. . . . But I told him, he's not getting his box back."

The day after Rizzo's faux retirement, he handed over his treasured shoeshine box to the crew of the John F. Kennedy. In turn, the crew presented it -- along with six well-used bristle brushes and an empty tin of brown Kiwi polish -- to the Staten Island Institute of Arts and Sciences for eventual display in the Institute's ferry museum inside the St. George terminal.

Still, Rizzo toted an identical, antiquated twin as he roamed the Lehman yesterday, puzzling some of the crew.

While politely declining a shine, Kathleen O'Connell, of West Brighton, offered the irascible bootblack a hearty hello on his return.

"I was glad to see him because there's a history there," she said. "He said, 'Staying home, not good.' I guess he was bored."

Hugo Munoz, the man with the black loafers, knew nothing of the pair's short-lived retirement. But he was nonetheless happy for a shine.

"Sometimes we look for these services but it's hard to find," said Munoz, a car service driver from Brooklyn whose vehicle was parked in the belly of the ferry. "It's an old tradition."

The return of the ferry shoeshine guys came, appropriately enough, on the heels of some of the season's sloppiest, snowy weather.

"One trip he had three guys lined up to remove salt from their boots and shoes," Ms. Mooney said.

The Staten Island Ferry continues to hum across the jelly-like waters, back and forth. The engine's reverberations still massage your feet. The smell of overcooked hot dogs still consumes the concession stand. And the ride still ends with the groan of massive vessel meeting wooden slip, the sound of journey's end.

But one sound has gone missing from the ferry experience these past few months. This sound: Shine! Shine! Wanna shine?

For more than 30 years, an Italian immigrant named Carmine Rizzo walked up and down the worn aisles of the ferries, calling out his services and hoping for the catch of an eye, the raise of a hand, a simple nod. Once summoned, he would place a small pillow on the ground and kneel before the patron, as if in supplication.

From this vantage point he could not see the glint of morning sunlight off Lady Liberty's torch, or gaze into the fog that seems to set the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge in the backdrop of a dream. There on his knees, all he saw were the words ''Life Preservers'' stenciled beneath the lips of scarred, dark-wooded benches; trouser legs; and other people's shoes.

He and a couple of other men from the Salerno region of Italy detected opportunity in the desire of businessmen to exude financial promise, down to the very tips of their shoes. These immigrants hawked and polished and buffed, marking the years through their faint reflections in footwear. One by one they disappeared, though, dying or retiring or returning to Italy, until there was only Mr. Rizzo, calling out shine, shine, above the ferry hum.

With the demand for polished shoes in decline, and the modest potential for making money, Mr. Rizzo retired four years ago -- only to return three weeks later. Then, in December, he retired again, telling The Staten Island Advance that at the age of 76, he saw no benefit in commuting from Whitestone, Queens, early in the morning to make as little as $2.50 a shine.

''This time I'm firm,'' he had said through an interpreter. ''I'm not coming back.''

The city's Department of Transportation had no choice but to advertise the availability of a city concession. It issued a 38-page document entitled ''Request for Bids for the Operation of a Roving Shoe Shine Service on the Staten Island Ferry Boats.''

The document detailed the potential of the enterprise, explaining, for example, that 65,000 commuters and tourists ride the ferries that chug to and from Manhattan and the St. George section of Staten Island. It asked bidders to ride the ferry, ''which is free, to view the passenger seating areas.''

It also laid out the ground rules for a ferryboat shoe shiner. The licensee ''may offer services with a short verbal announcement that includes the price of service (i.e. 'Shoe Shine! X Dollar Shoe Shine!'),'' it said, but may not be ''loud, offensive, misleading or unduly intrusive.''

For the right to get down on your knees, again and again, and polish the shoes of those whose faces are often concealed behind newspapers, the city suggested a minimum bid of $4,000 for the first year. Bids were to be submitted no later than 11 a.m. on Jan. 12, the document said, at which time they would be ''opened promptly.''

At 11 a.m. that day, city officials promptly opened nothing. ''We didn't get any bid,'' Tom Cocola, a transportation spokesman, said. ''It's as simple as that.''

What did this silence mean? Were up-and-coming entrepreneurs missing the opportunity of a lifetime? After all, people still wear shoes, and more than a few still want others to shine their shoes for them.

Perhaps there is something off-putting, even sad, about a shoeshine man without permanent station: a man who carries his wooden shoe stand and pillow through the aisles and decks of a swaying city ferry, waiting for the wave that permits him to kneel. If his presence evokes an Old New York charm, perhaps it is only to those whose shoes sparkle.

FOR nearly five months now, the Staten Island Ferry has borne the absence of the shoeshine man who speaks virtually no English. But the city recently announced that it was trying once again to solicit bids for shoeshine service on the ferries. Interested parties can submit their bids on June 1.

Word of this new solicitation for bids has reached a certain household on solid ground in Whitestone, where a recent retiree putters about, unable to relax.

''He's driving me crazy,'' said Angelo Rizzo of his father. ''Up the wall, sometimes.''

Some days Carmine Rizzo thinks no, the son says. But other days he thinks yes, yes, he should return to roving the ferry.

In 2000 Carmine Rizzo retired as a shoeshine guy on the SI Ferry but Carmine did not take a shine to retirement.

The ferry shoeshine guy was back in business, just three weeks after telling the city Department of Transportation (DOT) he did not intend to renew his long-standing concession contract to provide services inside the St. George terminal and aboard the boats.

But there he was yesterday morning, kneeling on his raggedy pillow, hunched over a pair of black loafers belonging to a well-dressed man sitting by the snack bar on the 10:30 Manhattan-bound Gov. Herbert H. Lehman.

"It's not good at home," Rizzo said in his halting Italian accent after finishing the job. "Working

three days only." As Rizzo cruised to Manhattan, his spitshine sidekick, Angelo Passero, was buffing his way to

St. George aboard the Samuel I. Newhouse, according to Lehman crew members.

Yesterday was the first day back on the boats for the shoeshine guys since Jan. 5, when Rizzo's $7,200-a-year DOT concession contract expired.

Apparently bored with a life of leisure, Rizzo recently signed a new one-year, $7,600 contract, effective yesterday, to provide shoeshine services aboard the boats three days a week, according to a DOT spokesman.

Last week, the DOT removed the decrepit shoeshine stand Rizzo once rented outside the ladies' room at the St. George terminal, the spokesman said. It was not immediately clear whether the stand will return.

Though Staten Island Ferry staples for decades, little is known about Rizzo and Passero. The pair -- who bear a striking resemblance to one another and are often confused as being the same man or brothers -- have long rebuffed interview-seeking Advance reporters.

Rizzo reportedly lives in Queens; Passero in Brooklyn. Both men hail from the same Italian province, Salerno, and communicate with passengers only in terse phrases of limited English.

When pressed for details on what exactly was "not good" about retirement, Rizzo said daily episodes of his grandchildren crashing on his sofa wore thin fast. "Sit and watch TV all day," he said, dismissing the very thought of idleness

with a wave of his large, weathered hand. Then, with a sparkle in his eye and a wry smile, Rizzo nodded emphatically

when asked if it felt good to be back on board.

Lehman crew members and ferry patrons also expressed delight at the shoeshine guy's decision to shelve retirement.

"I was shocked to see him," said a deckhand who lives on the South Shore but refused to identify himself. "It's good to see [the shoeshine guys] back. They've been here so long. They're like half the family."

"I missed him the three weeks he was gone," Colleen Mooney, of Port Richmond, a longtime ferry attendant, said of Rizzo. "He's like one of the crew. . . . But I told him, he's not getting his box back."

The day after Rizzo's faux retirement, he handed over his treasured shoeshine box to the crew of the John F. Kennedy. In turn, the crew presented it -- along with six well-used bristle brushes and an empty tin of brown Kiwi polish -- to the Staten Island Institute of Arts and Sciences for eventual display in the Institute's ferry museum inside the St. George terminal.

Still, Rizzo toted an identical, antiquated twin as he roamed the Lehman yesterday, puzzling some of the crew.

While politely declining a shine, Kathleen O'Connell, of West Brighton, offered the irascible bootblack a hearty hello on his return.

"I was glad to see him because there's a history there," she said. "He said, 'Staying home, not good.' I guess he was bored."

Hugo Munoz, the man with the black loafers, knew nothing of the pair's short-lived retirement. But he was nonetheless happy for a shine.

"Sometimes we look for these services but it's hard to find," said Munoz, a car service driver from Brooklyn whose vehicle was parked in the belly of the ferry. "It's an old tradition."

The return of the ferry shoeshine guys came, appropriately enough, on the heels of some of the season's sloppiest, snowy weather.

"One trip he had three guys lined up to remove salt from their boots and shoes," Ms. Mooney said.